Moody Bluegrass: A Virtual Reunion and the Enduring Legacy of the Moody Blues

Share

Crawdaddy.com

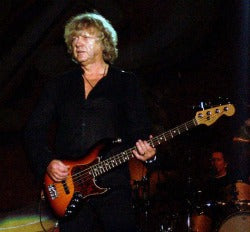

The Moody Blues just cruised past their 47th year as a working band, and they’re still on the road pleasing fans young and old with their impressive catalog. In recent years, the Moodys have returned to their roots as a rock ‘n’ roll band. They still play the songs from their lushly orchestrated psychedelic albums like Days Of Future Passed and On The Threshold Of A Dream, but thanks to the advances in musical technology, they can now play them on stage without carrying a symphony orchestra with them. Their most recent live album, 2005’s Lovely To See You, was recorded at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles and showcased a band that was still in fine mettle—hitting all the high notes and putting on an energetic show. Bassist John Lodge, 66, and

drummer Graeme Edge, who just turned 70, the two musicians who have been with the group through its many incarnations, recently spoke to Crawdaddy! about the band and its legacy between dates on their current world tour.

In Conversation With John Lodge

Many bass guitar players picked up the instrument because there were already too many guitar players in their band. Not John Lodge. Bass has always been his one and only interest. “I actually liked classical music when I was a kid,” Lodge begins. “In my school, we had a quiet period every afternoon, and they’d play records by the Birmingham Symphony, which is a great orchestra. I loved the music, but nobody in my family played and there were no instruments lying around the house. I did sing in the church choir, but that was it until I saw a few rock ‘n’ roll shows when I was about 11. I loved rock ‘n’ roll and got a guitar from a neighbor for about seven pounds. I learned to play it and I was hooked. I learned all the riffs from every rock song, but I was mostly playing the bass strings. That’s when I realized I wanted to be a bass player. The bass and drums were the engine rook of rock; the rest was the topping on the cake. You get a drummer playing with you and you lock into the rhythm, then you have the foundation for a band. You get a good singer on top of that and you’re on your way.

“The first bass I ever saw was a Fender Telecaster Bass, played by Jimmy Johnson, a guy in an American band call the Treniers. They did a concert in Birmingham, and I couldn’t take my eyes off the bass player. When I started playing in bands in 1960, I got a Fender Precision Bass. I’ve been using it ever since. It’s on all the albums and it still plays beautifully. It’s the love of my live, but it isn’t perfect for large concerts. I told the Fender people that I wanted to tweak the design a bit and worked with their guitar techs to come up with the customized Fender Jazz Bass I’ve been using for the past 10 years or so. The modern electronics give me better control over the depth and harmonics of the sound.”

With his beloved Fender Bass in hand, Lodge met Ray Thomas, another fan of American music. “I was 14 when I met Ray. We started playing the American rock songs we liked. At that time, every band in England was trying to play like Americans. All the early British rockers just covered American hits, with a few exceptions, like ‘Move It’ by Cliff Richards and the Shadows, and ‘Shakin’ All Over’ by Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. We went back and listened to the roots of the music, blues, country, folk, and R&B and slowly realized that we could write our own songs too.”

Lodge and Thomas put together El Riot and the Rebels, still playing covers of American hits. When the band broke up, Thomas put together another group, the M B Five. “There was a popular brewery in Birmingham called Mitchells and Butlers. We played in a lot of M and B pubs and hoped they’d employ us full time, but that was not to be. We did win a lot of the battle of the bands contests in Birmingham. When Denny joined and we became the Moody Blues, I was going to college in the daytime, and playing in the band night. When I was young, Birmingham was called Motor City UK, after Detroit. I’d wanted to be a car designer since I was seven, and went to college to study engineering. When the band took off, I had to decide between music and college, and I decided to stay in school. After I graduated, Denny left the band and Ray called me up. He wanted to know if I was ready to become a professional musician. He said we were going to write and record our own songs and stop doing covers. I rejoined the band, and we’ve been at it ever since.

“We left England and went to Mouscron in Belgium to write songs,” Lodge recalls. “We were making a plan for a new kind of band. We put together a 45-minute set of cover songs and 45 minutes of our own music and took them to clubs in France and Belgium to see how people would react. It was a time of huge experimentation. Before that, people went to clubs and danced. We didn’t want them to dance; we wanted them to listen to our songs. If we wanted to put in a rock tune or a waltz in middle of a set, we did it. We didn’t want to have any boundaries in the music. The work we did in Belgium planted the seeds that grew into the Moody Blues.

“By the time we recorded Days of Future Past, we’d gotten good at organizing ourselves. If we had a subject we wanted to write about, everybody would write two songs about it, then we’d pick the songs that fit together best. We did that for the first seven or eight albums, and it gave us a great range of music, with a panoramic view of the same subject by coming at it from many different angles.”

Although Days of Future Past became a worldwide hit and established the Moodys as bona fide rock stars, the album was recorded under false pretenses. The label wanted an orchestral record they could give away to record and stereo stores to demonstrate their new stereo recording technology. “Decca was promoting FFRR , which was their version of stereo. They wanted us to write lyrics to Dvorak’s New World Symphony for a pop/classical album. We said we’d do it, but when we got in the studio, we recorded all the songs we’d written instead. We left gaps for the orchestra to play on the songs. This was all done on a four-track machine. It was an incredible piece of technical work to put a stereo recording of an orchestra on top of what we’d done already.

“When the album was finished, Decca had no idea what they had. The head of classical music at Decca UK was Hugh Mendl, and the head of London in New York was Walt McGuire. We played it for them, and they understood what we were doing and became out mentors for the next 20 years. The CEO of Decca in the UK was Sir Edward Lewis, one of the great music men of all time. He only went into the studio twice in his life: Once to see Bing Crosby and once to see the Moody Blues. He wanted the music to be created without interference. He loved us, and that was the end of that. The record company got out of the way and put it out.”

Continue Reading...